| Issue 7 |

Lord Browne started by noting that Lord Avebury, representing the Lubbock Trustees at the meeting, was one of those rare individuals who had combined careers in engineering and politics. Too few engineers got involved in public life, but he hoped to show that in fact they had a unique set of views and perspectives that qualified them to make a greater contribution there than they actually did.

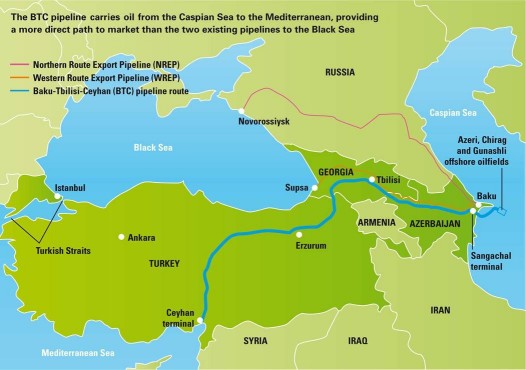

To illustrate this point he proposed to talk for about 20 minutes about a project he was involved in as Chief Executive of BP, the building of the BTC pipeline to take oil from the Caspian Sea to the shores of the Mediterranean. There would then be plenty of time for questions.

100 years ago, when the Department of Engineering Science was being founded, the Model T Ford was just being put into mass production. This started a transportation revolution that changed the world, giving billions of people access to personal transport, and bringing about the changes to working patterns, industry, roads, city layouts etc. that flowed from it. And it led to the growth of the oil industry, in which the speaker had spent most of his career. Engineers, he pointed out, don't just build things, they change the way we travel, live, communicate. So what should an engineer know, and be able to do, in order to handle these responsibilities? Clearly, mathematics and the physical sciences to start with, but also how to solve real-world problems, engage with communities, politics, economics and environmental considerations. There was a need for judgement, and for empathy.

The BTC pipeline, whose story he was about to outline, runs from Baku, on the shores of the Caspian in Azerbaijan, via Tbilisi in Georgia to Ceyhan on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey (see Figure 1). Its success depended on the abilities of engineers to solve all sorts of political, economic and environmental problems. The Caspian oilfield had been known for a long time, and there were about 3000 wells there even by 1900. But there was a need for a more effective way of getting the oil out, partly to reduce the number of tankers going through the narrow Bosporus with its vulnerable historic sites. The pipeline as built runs for more than 1000 miles, goes up to 3000 m above sea level in places, crosses 1500 rivers and roads, and cost $4 billion to build. And it is buried along its whole length.

|

| Figure 1: The BTC pipeline |

The route it takes is not the one that would have been chosen on the basis of mere physical geography, distance, gradients etc. A more direct route could have been found into Turkey through Armenia or Iran. But there has been hostility between Azerbaijan and Armenia for many decades, occasionally leading to military action. There was too much risk in taking the pipeline that way. And the situation between Iran and the USA ruled out that option too. So it had to go through Georgia. The Georgian authorities, though somewhat uncertain of their own political stability, were in no doubt of their strong position vis-à-vis BP, and of course exacted their price. All three countries through which the pipeline passes changed their leadership at least once during the construction period, so there was a good deal of re-negotiating of agreements, which had to be expressed in different languages and drafted according to different sets of laws. The engineering management team, 500 of them in 17 different offices, had to display remarkable diplomacy, sensitivity and negotiating skills.

There were inevitable risks of environmental damage, primarily from leaks. The possibility of these occurring had to be minimised, and means set up for coping with them if they did. The pipeline is buried in a trapezoidal trench, which is filled with a granular material intended to permit seismic movement, and designed to cope with a 1 in 10,000 year earthquake.

Although 750,000 people were affected in some way by the work, none was permanently displaced. 1000 landowners, owning between them 30,000 parcels of land in three countries, were disturbed only temporarily until the land covering was restored, and they were compensated. At the height of the work, 22,000 people were employed on it. 70-80% of them were local, and BP trained them for the purpose.

It is essential of course that engineers involved in such a project should recognise the limits of their own competence, and seek expert help when necessary, e.g. from wildlife specialists, human rights lawyers and archaeologists. There have to be trade-offs between conflicting interests, so it is inevitable that not everyone will go away completely happy.

It was time, Lord Browne suggested, to redesign the package that defines the term "professional engineer". They need to be taught to understand business, politics, public policy, and to be prepared to tackle real-world problems. An education that balanced creativity and scientific rigour with the need for practical solutions would surely attract the most talented students.

Almost as an afterthought, Lord Browne pointed out that when the Model T Ford was being put into production, there was a need to find a suitable fuel for it, that could be made widely available. It could equally well have been either gasoline or ethanol. The choice fell on gasoline, partly because it was cheap, but also because the American "Prohibition" policy of the time restricted the production of ethanol. This was a highly significant choice, not only for greenhouse gases, but also because for many decades gasoline needed the addition of lead tetraethyl to improve engine performance, which inflicted substantial damage on human health until it was given up.

Finally he expressed the view that the greatest challenge now was preventing climate change, where engineers could have a profound effect on the policies to be adopted. Engineers cannot predict the future, but they can certainly affect it.

The audience then presented the speaker with a long series of questions, the replies to some of which brought out further interesting facts. The questions included:

The full lecture, and the ensuing question-and-answer session, can be seen on the Department's website: www.eng.ox.ac.uk/events/centenary/videos.html

| << Previous article | Contents | Next article >> |

| SOUE News Home |

Copyright © 2008 Society of Oxford University Engineers |

SOUE Home |