| Issue 10 |

March 1985 found me at a low ebb. Two years earlier a colleague and I had started Microtrol and we had just reached the parting of the ways.

The company had been launched with the objective of offering design engineering services to businesses who were not in possession of their own electronics department, placing strong emphasis on working with the customers, understanding their needs and pooling our engineering skills with theirs. Initially we targeted data logging to complement the then new range of instruments appearing with serial communications. However as initial enthusiasm became tarnished with commercial reality it began to look as though it perhaps hadn't been such a great idea after all.

As I had been responsible for the technical direction of the business, the marketing and administration were unfamiliar territory for me but needed to be taken in hand if the business were to survive. A few weeks later my wife, heavily pregnant with our fourth child, was seeking out a new accountant whose advice was that I should continue to run the business whilst looking for a new job. The running of the business left little time for job seeking but, one year on, together with two loyal employees we were still at work and had moreover posted a first profit. Fifteen years later I was able to invite the same accountant to the company's newly acquired business premises in the Worcestershire countryside and today the company is turning over just short of one million, providing a good living for its small number of employees and having a portfolio of customers who, almost without exception, we are pleased to class as good friends.

In the early days some business was generated through advertising but the majority came from contacts already known through our previous positions as sales engineers for temperature control manufacturer Eurotherm Ltd (now part of the Invensys group).

The first products were designed around the emerging range of personal computers, adapting their operating systems to fulfil our needs. Hard to believe how advanced this seemed at the time, perhaps demonstrated by the picture showing one of our early data logging systems which conceals (not very well) a Commodore PET, a BBC model B, a 'Tangerine' and a specialist 64 colour graphics card. However, it rapidly became apparent that we could not be competitive and flexible without our own processor cards and we therefore set about the design of these, painstakingly tracking the boards using rubber tape. Three years later and by then in possession of our first PC with a massive 10 MB hard drive (who could need more!) we purchased our first PCB CAD software, putting us in a position to generate new boards customised to project requirements. This package served us well for a number of years with business comprising a selection of large projects underpinned with a steady demand for our original printing logger and a range of signal and protocol converters to smooth the flow of funds.

|

The next significant change in design occurred when we attended a Department of Trade and Industry seminar which introduced us to the new and highly versatile processors - microcontrollers. These devices with on-chip ROM and RAM opened new possibilities and have been the bedrock of our products since then. Microcontrollers moved digital electronics into an extended range of markets not accessible to the conventional bus based processor systems of the time. Our first microcontroller product was a digital thermostat for an air conditioning system, commissioned by a distributor for one of the major Japanese air conditioning companies. Without microcontrollers this product would never have been viable but as it was we were able to hit the target price and with an acceptable margin. We were not to know at the time but this was a massive milestone for the company. We were subsequently asked to design larger and more complex systems to link complete air conditioning complexes to Building Management Systems and today we directly supply that same air conditioner company with a wide range of specialist interfaces for their equipment. The products control the environments of hotels, offices, shops, hospitals and many industrial premises. As volumes have grown we have needed to put in place structures to allow a small company to handle quantities. Our latest departure, a track-day logger for motorcycle enthusiasts, takes advantage of these as we venture into the consumer marketplace. Using a combination of rate gyroscope, accelerometer and GPS, the unit logs position, speed and, uniquely, the lean angle of the bike - a simple concept which has proved surprisingly challenging to achieve. A picture of the unit is shown ready for action. It is all a long way from the PET-BBC-Tangerine of 1985.

|

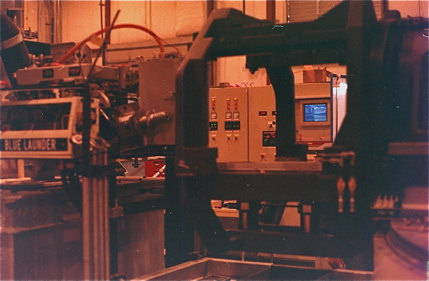

At the onset the plan was to offer engineering services in response to companies' requirements and we targeted these around a configurable, printing data logger, dubbed an 'intelligent printer'. Before long we found ourselves being encouraged off piste and on to "more interesting" projects. An early coup was gaining involvement with an engine casting/motor racing company to assist them in computerising their aluminium casting process. The process used a ceramic eddy current pump, originally designed to pump sodium in nuclear reactors, with mould level being detected by a custom designed capacitive sensor. This project was to occupy us intermittently for several years from the original (inevitable) BBC model B to the eventual OS/2 based installation of three casting stations - each producing one engine block per minute - at one of the major motor manufacturers in Detroit. The picture below shows the US pilot plant with the control panel viewed through the casting clamp and the pump launder nozzle to the left. Other stimulating projects included the control of a 150 tonne, 3 m diameter hydraulic press to a travel accuracy of 0.1 mm in 2 m; the transmission heat treatment line at a prestigious West Midlands 4x4 motor company; a winder system capable of smoothly winding 25,000 m reels of 12 micron, 2 m wide laminating film; and substantial work on ceramic cooker hobs to provide quick boil, automatic pan temperature control for frying and boil-dry detection.

|

These were the one-offs, very interesting but leaving a sort of post-natal depression at the end where the elation of sending the final invoice was tempered by a sadness at the sudden loss of involvement and possibly the question of where the next salary cheque might come from. The more continuous business whilst perhaps not quite so exciting presented its own challenges as we developed control packages for a variety of machines including the cold forming of coil springs using up to 28 mm diameter wire, a range of electronic systems for the testing of the properties of plastics (viscosity, friction, impact strength etc.) and even the control of crematorium furnaces.

In all of these projects, and many more, I have been grateful for the wide grounding I acquired from the Oxford Engineering first degree and my DPhil experience. The ability to discuss engineering aspects outside the electronics element has been invaluable and is a great asset in gaining customer confidence. It also removed much of the fear of the unknown which may otherwise have accompanied a number of projects.

The cross-disciplinary capability is well demonstrated by the project shown below. Here we had been asked to produce an automatic test rig for low pressure boiler flue switches, generating both positive and negative pressures from a compressed air line using a Pitot vacuum pump. The electronics were relatively trivial but the associated pneumatics less so. Although we were able to pick some ideas from the original old and decaying rig we were unable to dismantle sealed components, in particular the large 'plenum chamber' shown in the centre. No one seemed to know exactly what was inside so we took an educated guess and tests with the aid of a large coffee tin and improvised baffle plates showed our guess to be promising. One of our customers then assisted us, manufacturing the official parts and the project moved to a successful conclusion.

|

Of course a business is not just about hardware and applications. The third element in the mix is people. The right mix of capable and effective people is the difference between an enjoyable and vibrant business and one where stress and disillusion reign - and without doubt, the former has the better prospects. The requisite skill requirements need to be met but it is not necessary for everyone to be highly qualified. People bring their own skill sets, which will grow with the job, and with the right encouragement this process should be stimulating and fun rather than pressured. In our first year we advertised in a local shop for a technician. A couple of days later a mum appeared ushering in her 16 year old son fresh from school. He seemed pleasant and capable so we took him on. Paul is still with us, now a highly accomplished printed circuit board designer and a key member of the team.

The people link doesn't stop in house. Good partnerships from supplier through to final customer promote an efficient wealth generation route. A recognition that everyone needs to make a sensible return helps to keep the relationships long term. Everybody responds well when treated fairly and requests for special performance when needed are much more likely to be met. Finding good, new suppliers and customers is time consuming and time is a very precious commodity. We have always tried to work with customers as if we were a part of their company, making sure that we fully understand the problem they have and how we may be able to help. This puts us in a position to make additional suggestions to enhance the product - on the basis that the more they sell the more we will sell. In general it seems to have worked well.

Running a business inevitably will have its ups and downs. When things go well it is hugely rewarding but you do need to be prepared to ride the downs. As a competent engineer your services should always be saleable. The engineering world needs logical, informed thinking and that is not always as readily available as might be assumed.

However, simply solving specific problems has limited growth potential. The aim should be to capitalise on the solutions wherever possible - think once and sell it many times.

Over the years we have mentally drawn up a list of Do's and Don'ts - this does not mean to say that we have not done any of the Don'ts or done all the Do's first time but for what it's worth here are a few.

Firstly, don't try to be good at everything. Do what you do well and leave others to do what they do. Preferably do the things that you can do and others can't - why invite unnecessary competition?

Be flexible. Don't avoid something simply because you haven't done it before. Push yourself and follow up (at least briefly) all reasonable enquiries - you never know which box may contain the golden egg. New challenges are exciting and provided the risk factor is not too great they will ward off any threat of boredom.

When something doesn't want to work try explaining to a colleague how you have tackled the problem. It's amazing how many times you will solve the problem yourself half way through the explanation!

Present products and services professionally. The small company will tend to be the focus of attention when everything is not going quite as planned. Good presentation generates early credibility - which, one would like to think, will prove to be fully justified.

Hopefully your lucky break will come - but keep in mind Thomas Jefferson's view:

"I'm a great believer in luck and I find that the harder I work, the more I have of it."

| << Previous article | Contents | Next article >> |

| SOUE News Home |

Copyright © 2011 Society of Oxford University Engineers |

SOUE Home |